Txus

Figuring out the thing

Latest posts from double dissent

-

From many to one

Jan 02 ⎯ In the last post we used GPUs to add two vectors, element by element. It’s what we call an embarrassingly parallel problem, but you might be thinking: is this all that GPUs are suited for? Doing independent things in parallel with no coordination? One operation often arising in LLM inference is summing all elements of a vector. On a CPU, you would do this: How would you parallelize this? Each value is added to a common accumulator. If you’ve been around the block for a while, you’ll recognize this as a fertile ground for a classic race condition, also known as a lost update problem. If we were to naively spawn a bunch of workers and process elements independently, at some point two workers would both read the current value of acc at the exact same time, add their respective values onto it, and the last one to write would win the race—the other would lose its update. To solve this in CPU-land, you’d need some sort of coordination primitive like a lock: while one worker performs its read-then-update, others need to wait their turn. This contention kills performance. But there is another way: each worker can take ownership of a section of the work to do, complete it in private, and then we can aggregate the partial results later. This is called privatization. (1 + 2) + 3 = 1 + (2 + 3) After each worker reduces its workload to a single partial sum, adding those partial sums will always give the correct result. And because it is commutative, the order we perform that final aggregation does not matter. In practice, floating-point addition is not commutative, as explored in this Thinking Machines article about non-determinism in LLMs, but that’s a can of worms for another day. So yes, moving your code to the GPU can change the results of your reductions! Welcome to this beautiful mess. Summing vectors on the GPU In practice, we want to sum batches of vectors independently, say a batch of 65536 vectors, each of length 2048. The result will be 65536 independent sums. This should be a beefy enough workload to saturate the GPU's resources and keep us warm for a bit. There are many ways to organize this work, but we’ll keep it simple by creating as many thread blocks as vectors we need to reduce. This way, each thread block is responsible for one vector, and will write a single number as a result. When you launch a CUDA kernel, you tell it your problem size so the GPU can allocate compute and memory accordingly. This is called a launch grid, which is composed of many thread blocks, which are composed of many threads. A thread actually runs your kernel. There are no limits to how many blocks grids have, but hardware imposes a limit on how many threads each block can have: 1024. The most naive approach: atomicAdd Technically, the easiest way to do this is have each thread read a value from global memory and add it to the output with an atomic write. But that is a terrible option! The GPU will serialize all writes to the same value, so we might as well be using CPUs and locks. We need a more parallel-friendly approach. Hierarchical reduction The plan is to do log(N) iterations where each thread does one addition. At the end, the first thread contains the sum of the entire N values. Beautiful, no? We only need N/2 threads. You'll notice in this picture, though, that after the first step, when each of the 8 threads contains a partial sum, thread 0 needs to add itself to the value at thread 4. How can a thread get the value from another thread? Turns out, thread blocks have access to a shared pool of memory that only threads within that block can read and write to. It is known as shared memory or L1 cache, and it’s entirely programmer-managed! It is also ten times lower latency than going to global memory. This memory hierarchy is a powerful tool—memory closer to the computing core is orders of magnitude faster and smaller than the next one further away. With careful planning, we can both perform fancy coordination while avoiding contention and unnecessary roundtrips. So our plan is: Choose the number of threads per block, for example, blockThreads = 512. Accumulate chunks of blockThreads values from global memory into shared memory Perform reduction hierarchically in fast shared memory Write sum back to global memory Let's give it a go! Not too bad. But to progress from here, it’s time to let you in on a little secret. The Hidden Code There is a hidden code CUDA programmers live by, a set of commandments. They encode arcane knowledge about living in harmony with the physical hardware that actually runs the code, instead of blindly trusting the leaky abstraction that is the CUDA programming model. Those who ignore the commandments are doomed to Slow Limbo, where kernels take forever to run while GPU compute sits idle. Those who follow them, some claim, will see their FLOPs/second go up. #1: You Shall Coalesce Memory Accesses This is one of the most important principles. The CUDA code we write runs on compute cores in an SM (Streaming Multiprocessor), physically far from global memory (VRAM). When a thread reads or writes memory, the SM groups those operations to better utilize the memory bus. It can only do this if they are coalesced. Memory accesses are coalesced only if threads access contiguous memory addresses. If thread 0 accesses memory position 16, thread 1 accesses position 17, and thread 2 accesses position 18, it is a coalesced access and can be done in a single trip to memory. If you look at our kernel, we respect this principle in the first reduction stage: Thread 0 (tid == 0) adds offsets 0 and blockThreads in a vector. Thread 1 (tid == 1) adds offset 1 and offset blockThreads + 1 in a vector. Etc. This causes one coalesced read per loop iteration. In the log(blockThreads) hierarchical reduction: Even though at each loop iteration we halve the number of working threads by 2, accesses to and from shared memory remain coalesced. So we are doing okay on this front. What else can we learn from the hidden code? #2: Not All Memory is Created Equal SMs physically have an L1 and L2 cache inside (the smaller number means it is closer to the compute). We are using shared memory heavily, with typical latencies around 30-40 cycles, 10x faster than global memory. So far so good. But there is an even faster memory we almost never think of as such: registers! Each thread has a very small number of allocated registers that are fast; their latency is 1 cycle. That is 30x-40x faster than accessing shared memory. As the proverb goes: Don’t go back and forth to global memory if you can do it in shared memory, and Don’t go back and forth to shared memory if you can do it in registers. In particular, the first strided accumulation we could do from global memory to registers entirely! Then, do a single write to shared memory: A 10% speedup! The elders are onto something. But surely we can do more. There is a technique called warp reduction that we might be able to use. What is a warp, you say? Ah, I forgot to tell you: #3. Threads Aren’t Real Well, they sort of are, but it makes no sense to think of them as truly independent. An SM, like any computing device, has a scheduler. When you launch a grid, you assign a backlog of thread blocks to work on, and the SM decides what to launch when—and since it is quite smart, it likes having a large backlog of things it can multitask on. But the SM scheduler cannot schedule work onto individual threads. Instead, it schedules work onto warps: groups of 32 threads, in a SIMT fashion (single instruction, multiple threads). All threads in a warp execute in lockstep, and there is no way to avoid that. In fact, if you add a conditional like if (tid == 0), you’ll still take up an entire warp to run, but only the first thread will do anything. The other 31 threads will stall and wait. If there was an else branch, the scheduler now has to issue 2 instructions in sequence: one for the first thread, and one for the other threads in the warp. Warp reductions So what are warp reductions? They are a technique that benefits from special coordination operations that threads in a warp can do, in a single cycle, without locks, shared memory, or anything else. For example, we can do a hierarchical reduction entirely in a warp! __shfl_down_sync takes what is in the thread offset to the right of us and puts it into our val register. We can use that to reduce 32 values onto 1, and each of the log(32) steps takes 1 cycle to move things around. Awesome! Putting it all together Let’s implement our fancy new warp reduction in our kernel. To do that, we’ll cut the shared memory reduction short until we have a warpful of values (32 values). Then, we’ll reduce those with a fast warp reduction. What? 1 microsecond faster. After all, didn’t we save 5 calls to __syncthreads (the final iterations, 32 down to 1)? I’m going to complain at the CUDA Elders Council. I'm back. They told me to re-read the third commandment and atone for being such a silly goose. Since threads aren’t real, __syncthreads is actually a barrier different warps arrive at, not threads. The final iterations we saved happened within a warp anyway! So putting such a barrier when only one warp is active is a no-op. Time and again, truly thinking about the hardware from first principles helps anticipate which optimizations are likely to have an effect. The commandments are useful guides, but grounding them in empirical data from actual hardware is always mandatory.

-

How to add two vectors, fast

Dec 27 ⎯ I’ve been building a Llama 3.2 inference engine aptly named forward (purely as an excuse to stop procrastinating and learn modern C++ and CUDA), from scratch. Were I reasonable, I would not have decided to build a tensor library first, then a neural network library on top of it, and finally the Llama 3.2 architecture as the cherry on top. But here we are. The first milestone was getting Llama to generate tokens correctly on the CPU first, with every activation of every layer matching the Huggingface Transformers inference output. Milestone achieved! The next milestone, which I’m currently starting, is getting it to run as fast as I can on my NVIDIA GPU, an RTX 5090. The very first kernel I wrote is a timeless classic: adding two vectors element by element. Walk with me. Wait, why are you running away. Adding two vectors on the CPU Let’s start with a baseline to convince ourselves whether using a GPU is worth it in the first place. We want to add fairly large vectors, at least 134M elements each. This reflects the kinds of vector additions we will be doing during real-world Llama inference. Plus, each element will be a bfloat16 number, which for this article is just like a floating point number taking up 2 bytes of memory (16 bits). On the CPU, that means creating a blank output vector of 134 million elements, iterating over the input vectors to add their elements, and write the result to the output vector. (I’ve removed extraneous details like templating and broadcasting for legibility, but you can check the actual CPU implementation in the repo if you’d like your eyes to bleed.) Let's benchmark it. We will measure everything with a single throughput metric: FLOPs/s (floating point operations per second). Each addition is a floating point operation, so we will perform 134M of those and see how fast it is. It took 135 milliseconds to do all the additions, yielding just under 1 GigaFLOP per second of throughput. 1 GigaFLOP is 10^9 FLOPs (1 billion, in U.S. parlance). Not bad, right? Actually pretty bad. We are using a single CPU thread to do all the additions sequentially, but the additions are independent of each other. Can we parallelize without breaking our brain too much? Let’s try using OpenMP, which only takes adding a line before our for loop. It will magically spawn a bunch of threads and split the work between them: A 2.4x throughput increase with one line of code? Sign me up. But surely we can do better using these expensive NVIDIA heating devices. Let’s dust off the CUDA books and make our GPU go brrr. A simple CUDA kernel This looks pretty similar to our CPU version, but without the for loop. This function will run in a separate CUDA thread for each of the 134M elements—so all it needs to do is figure out which element idx it is responsible for, read one element from vector_a and one from vector_b, add them up, and store them in out. CUDA lets us decide how to split the work, how many threads we need, etc. We need one thread per output element. Threads are organized in thread "blocks," which are laid out in a "grid"—don't worry about this, it's arbitrary, but we need to tell CUDA how big our thread blocks are and how many of them we need. We can launch our kernel by converting from our bfloat16 type to CUDA’s equivalent __nv_bfloat16 and telling CUDA what launch grid configuration we want: Let us benchmark against the baseline: Just over 1 millisecond! Our naive CUDA kernel is around 49x faster than the parallelized CPU version. But how good is that? How can we know whether our expensive heater is being utilized to its full potential? Benchmarking against our potential To answer that question, we have Nsight Compute, or its CLI version called ncu, which comes with the CUDA Toolkit. Let’s profile our kernel with it, and look at the first section, called GPU Speed Of Light Throughput: SM stands for Streaming Multiprocessor, a collection of CUDA cores, a scheduler, and other details we do not care about right now. My GPU has 170 SMs, with 128 CUDA cores each. Let's first focus on Memory Throughput and Compute (SM) Throughput. These percentages show how well our kernel utilizes available memory bandwidth and compute, respectively. From the theoretical peak compute throughput, we are getting only 19.20%. That means, 80.80% of the time, our CUDA cores are sitting idle, waiting, not computing anything. Before we call NVIDIA and ask for an 80% refund, let’s ask ourselves. What are these precious CUDA cores waiting on? Looking at the kernel again, we can focus on what it is actually doing: Each thread: Loads one element from vector_a from global memory (commonly known as GPU VRAM) into a register. Loads 1 element from vector_b from global memory into a register. Adds them up and stores the result in a register. Stores the result from a register into out , which is also global memory. The CUDA cores only compute in step 3. Before that, it must wait for steps 1 and 2, and afterward, it must wait on step 4. Adding two numbers takes 4–6 cycles, whereas memory operations to and from global memory (VRAM) take 200–400 cycles, orders of magnitude slower than the addition itself! Fortunately, GPUs are excellent at hiding latency by running more threads while others wait on memory, but still. There must be something more we can achieve with our fancy CUDA programming skills. A fancy kernel Let’s start with data movement. Each thread is currently loading a single bfloat16 value from each vector, but since we are making the trip to global memory anyway, why can’t we carry more stuff back? Like getting eight bfloat16 values at a time? Loading 8 bfloat16 values in one go The way we can do that is by pretending we want to load a 128-bit value, and then slicing it into our 8 bfloat16s. Memory is laid out linearly, so we can get away with that! We tell CUDA, “I want to read a pack of four 32-bit integers from global memory.” We then reinterpret this as a pointer to an array of bfloat16 values: Now we can perform eight additions. Or can we get away with fewer instructions? Doing two additions for the price of one Turns out there is a packed bfloat16 type called __nv_bfloat162 (notice the 2 at the end, which means it contains two bfloat16s). We can add two __nv_bfloat162 values to do two additions in parallel with a single instruction this way. All we need is to change how we interpret the original uint4 packed value: Then, when adding __nv_bfloat162 values, we add two __nv_bfloat16s in parallel with a single instruction. Nice! Our kernel now looks like this: Let’s benchmark and get ready to get paid the big bucks. What? Only 10 microseconds faster after doing a PhD on the CUDA math API docs? Compute-bound vs memory-bound kernels How can we make sense of this? A useful concept captures the kind of kernel we are writing: How much compute do we do for each byte we read or write? In our case, it is one add instruction versus two 16-byte reads and one 16-byte write: 0.021 FLOPs/byte. We are basically just moving memory around the whole time, occasionally performing a tiny amount of compute. It might seem wasteful, but there is little we can do about it—it is exactly what our kernel needs to do. Our kernel is memory-bound, meaning it is limited only by memory bandwidth (1.7 TB/s in my GPU), not compute. Why isn’t the fancy kernel faster than the simple one? Recall the GPU Speed of Light Throughput table? We are utilizing the memory bandwidth close to optimally already, which is why loading more bytes at once makes little difference. As per the additions with the __nv_bfloat162 packed type, we perform two additions with a single instruction, which bumps our Arithmetic Intensity to… 0.042 FLOPs/byte. Compute is such a tiny part of our kernel that it does not matter if we do it twice as fast. We are still memory bound. Additionally, our more complex kernel uses more registers—a limited resource that, if abused, limits how many concurrent threads can run on an SM, so occupancy decreases. There is no free lunch. Conclusion GPU optimization is both an art and a science, but it pays off to learn the specific hardware you are targeting, formulate and test hypotheses, and always measure everything. Another win for the most widely applicable meme of all time, I guess.

-

You are not the code

Dec 20 ⎯ It was 2016. I was listening to Justin Bieber's Sorry (and probably so were you, don't judge), coding away at my keyboard in an office building in Canary Wharf, London. We were a small team working on a complex internal tool for power users. Our tools were Clojure and ClojureScript, which we wielded with mastery and pride. The great thing about building for advanced users is that they are as obsessive as you are about their own domain and will seize the edge wherever they can find it. So you build, they adopt early, you get feedback, and the cycle continues. It is a powerful feeling. The platform we were building was meant to visualize and sift through tons of data, slicing and dicing it to make informed decisions quickly. We provided a few common views and predefined filters, designed by our invaluable Product Owner who used to do our users' job—he understood deeply what they needed. One day, I got an idea. (The smartest and poorest decisions of my life both begin alike, as it turns out.) I wanted to craft a sharp knife and entrust the users with it. I was going to design a simple query language based on boolean algebra. A week went by. Then another. Bieber on repeat, living in a continuous state of flow, my regular life put on hold. All I could think of was this language, and how powerful our most advanced users would feel using it. After a couple of weeks, I was ready to demo the feature branch to Manish, my manager. At that point, he knew me well enough to know I hadn’t been doing what I was supposed to be doing, and that it was wiser to ask instead. “What are you up to these days?” Filled with pride, I told him I wanted to show him something cool. He smiled and grabbed a seat next to my desk. "Go on," he said. He immediately noticed the new text field above the data display. I typed a complex boolean query, and voilà! The data I wanted was there, almost instantly. Without stopping, I continued explaining all you could do with this powerful language. Users could save their own queries to use later. The interface was fairly self-discoverable, with syntax highlighting and readable errors explaining how the queries were meant to be written. “This is very cool,” Manish said with a smile. Pride swelled in my chest. “However… we are not going to ship it.” His demeanor turned more serious, with a hint of kindness. I frowned and said incredulously, "What? Our users are power users. They deserve at least to try this! If they do not like it, we can roll it back." “I get it. But this is not the direction we will take right now.” There was no malice in his voice, just kindness and empathy for how important this was to me. He did not put a hand on my shoulder, but I almost felt it. In that moment, a rush of feelings overcame me. I sensed a fire starting to roar in my belly, one that could easily burn down the entire building. But then, a sudden calm set in. I went to the terminal and slowly typed the command to delete my entire feature branch: Then I hit enter and braced for grief. But it never came. Instead, relief took its place. The code was gone, but I was still there. And with me were those two weeks of pure joy, focus, flow, learning, and growth. And new knowledge about building languages, too. For the first time in my career, I understood all at once: I am not the code. The code is an artifact, a byproduct of an ongoing process. That ongoing process is my growth as a programmer, as an eternal student of everything, as a person. I also understood that I had been carrying all the code I had ever written, petrified into my identity. If you questioned my code, you questioned me. If my code was broken, a part of me was broken too. Just a few years earlier, that whole situation would have unfolded differently. But instead, a moment of lucidity and a simple terminal command taught me one of the most valuable lessons in my career.

-

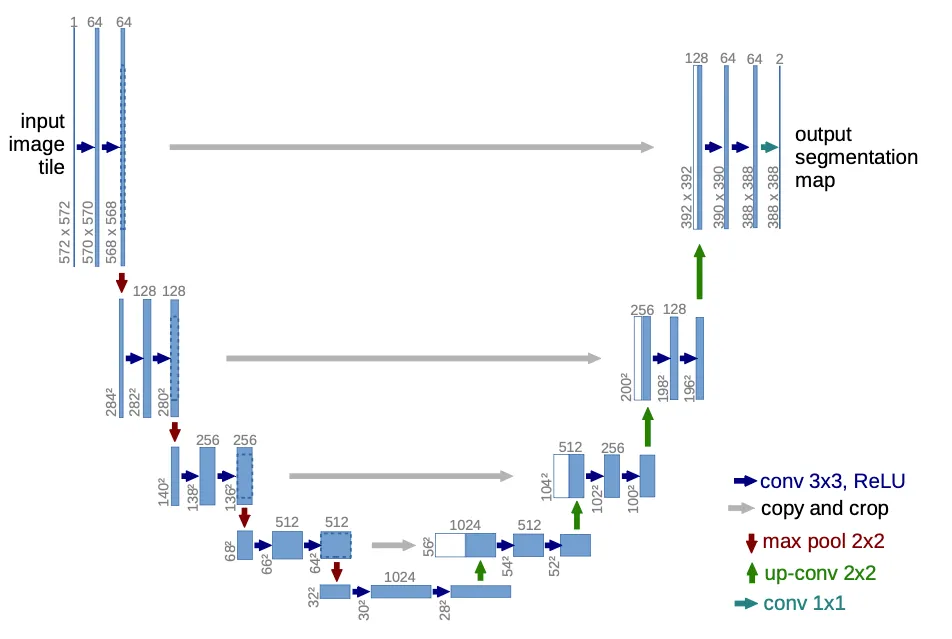

Reproducing U-Net

Jun 23 ⎯ While getting some deep learning research practice, I decided to do some archaeology by reproducing some older deep learning papers. Then, I recalled (back in my fast.ai course days) Jeremy Howard discussing U-Net and the impression it had on me—possibly the first time I encountered skip connections. So I read the paper and wondered: Is it possible to reproduce their results only from the paper, and perhaps even critically examine some of the claims they make? The full code is available on GitHub if you’re curious, but I thought it would be better to walk you through my adventure. Let's go! Background U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation came out in 2015. Although they released their code (which uses the Caffe deep learning framework), I did not look at it on purpose. It’s not because I can’t read C++ to save my life; it’s part of the challenge—reproduce U-Net only from the paper. Let’s use our own eyes to read the words and look at the pretty pictures! The original U-Net architecture diagramAs the title of the paper suggests, U-Net uses convolutional networks to perform image segmentation, which means it takes an image as input with things in it and tries to predict a mask that differentiates the things from the background (or from each other, if it is multi-class). It first puts an input image through a contraction path, where resolution decreases but channels increase, and then back up through an expansion path, where the opposite happens, ending up with a reasonably large image (but smaller than the input! more on that below) and a single channel (black and white). A first look at the data Here is a sample from the first dataset (which we call EM, for electron microscopy). It represents a cross-section of cells, and the mask differentiates cell bodies (white) from their membranes (black). A sample from the electron microscopy datasetBut why is the mask cropped, you may ask? Because of how convolutions move over an input image, even though their receptive field (what they see) is the entire input image, the output feature maps are a bit smaller (unless you use padding). After many down and up-convolutions, the network's output will be smaller than the input, so our dataset must account for that: for an input image of 512x512, we can only predict a 324x324 output mask, which is necessarily a center-cropped version of the original full-size mask in the dataset. The way I found out about this was the hard way, of course. When I first saw the EM dataset, which consists of input images and output masks all of 512x512 px, I naively tried to just resize down the output mask to fit the network's output, and it did not learn at all. Looking around, I saw some people suggested padding the expansion path with zeros to make the residual connections fit (more on that later), which seemed to work. However, the paper mentioned none of that padding, so I thought something was off. The penny dropped when the paper mentioned their overlap-tiling strategy. To process arbitrarily large images regardless of GPU VRAM, we must process images one fixed-size tile at a time. And if for any input tile we can only predict a center-cropped mask, we won’t learn to predict the masks in the corners! What a waste of good, valuable data. To solve that, our dataloader just needs to select a random output mask tile (even if it’s at the top left corner) and then make up the original input image that would predict that tile. If the mask tile was in some corner, we’ll just make up the surrounding context by reflecting the original image. A bit hand-wavy, but hey, that’s deep learning for you! Even though the architecture image is pretty self-explanatory, I found a couple of caveats worth mentioning: It assumes an input of 572x572 px, which I used to sanity-check the feature map sizes after every convolutional layer and pooling operation. The EM dataset’s input is 512x512 px, however. The paper mentions a dropout layer "at the end of the contraction path," though it is not pictured. I decided to put it right before the first up-convolution, but it is unclear where they actually put it. Model Implementation Here is the model code: Let’s look at the forward pass in detail. The contraction path is a series of Conv layers (each with two 3x3 Conv2Ds and ReLU activations) with max pooling in-between, which halves the resolution. As we go down the contraction path, notice that we save the Conv activations (before max pooling) in a residuals list. As per the architecture diagram, we will need to concatenate those in parallel to their counterparts in the expansion path. Again, since the counterparts will be of smaller resolution, the residuals will need to be center-cropped. At the end of the contraction path, we do a dropout and go back up through the expansion path, concatenating the contracted channels with the expanded ones. This concatenation effectively provides a high-bandwidth residual connection for the gradients to flow back. Finally, an output convolution gets the final predicted mask with a single channel (black and white). Loss Function The loss function is cross-entropy (or equivalently log-softmax plus negative log-likelihood), but there is a twist. On the EM dataset, they introduced a weighted loss with a synthesized weight map that uses morphological operations on the original mask to highlight the borders between cells: The synthesized weight map highlights the borders between cellsThis way, the loss is higher around cell borders, forcing the network to work harder to get those right. Coming from the Holy Church of Gradient Descent, this looks like a cursed hack, so I added it to my list of assumptions/claims to verify. Training Regime For training, they use Stochastic Gradient Descent with a momentum of 0.99, though they do not mention a learning rate (I set it at 1e-03). I wondered, "Why not Adam?" so another one for the bag of things to verify. Their set tile size was 512, which is essentially no tiling. Data Augmentation Since the datasets are very small (30 training images in the EM dataset!), the authors of the paper rightly put a lot of effort into data augmentation, settling on a combination of: Tiling: for a given image, as long as the tiles are smaller than the image, there are several tiles. The authors do claim, though, that to maximize GPU utilization, they favor larger tiles over larger batch sizes. At face value this makes sense from a GPU utilization standpoint, but because I was not sure how it might affect the final loss, that goes into my bag of claims to verify. Elastic Deformations: This one is fun! They warp the images with realistic deformations you might see in cells, providing more variety so the network does not overfit to the same-shaped cells. Dropout at the end of the contraction path: just to be sure. It is important to note that those 30 training images are very highly correlated, too, since they are consecutive slices within one single 3D volume. So it makes sense to deploy every data augmentation trick in the book. Expected results So, to reproduce the paper, what results are we matching? The authors trained their architecture for three segmentation challenges: 1. EM Segmentation Challenge 2015 (with the EM dataset, generously uploaded to GitHub by Hoang Pham). They are evaluated on Warping Error (0.000353), Rand Error (0.0382), and Pixel Error (0.0611), defined in the paper. 2. ISBI cell tracking challenge 2015 (PhC-U373 dataset, available here): they achieved an Intersection Over Union (IoU) of 0.9203. 3. ISBI cell tracking challenge 2015 (DIC-HeLa dataset, available here): they achieve an Intersection Over Union (IOU) of 0.7756. As it turns out, the test sets for these are publicly available, but the test labels are not. One is supposed to send the predicted probability maps to the organizers and get back an evaluation result. Unfortunately, ain't nobody got time for that (probably least of all the organizers), so we’ll have to take the authors’ word for it. To make sense of anything, we will have to settle on a lesser metric: loss on a validation set, which we will set at 20% of the training set. As I’ve mentioned, the datasets are highly correlated, so leakage is guaranteed, but it is literally the best we can do with what we have, short of hand-labeling the test set myself. Experiments All experiments are trained for 4K update steps, with batch size 4 and 512x512 tiles (so, 1M pixels seen per update), on 80% of the training set. We report training loss, validation loss, and IOU on the validation set. We also torch.compile the model for extra speed. After running the baselines, I dump the bag of things to verify, and the questions that interest me are: Authors claim that larger tiles are better than larger batch sizes. How do tile size versus batch size compare, keeping pixels seen constant? [For the EM dataset only] Weight maps seem like an awkward inductive bias. Do they help? Would Adam work better than SGD here? Datasets We already introduced the EM dataset with the synthetic weight maps: The synthesized weight map highlights the borders between cellsFor reference, the other two datasets are PhC-U373 (you can see the reflected bottom part in this one): A sample from the PhC-U373 dataset, with vertical reflectionAnd DIC-HeLa: A sample from the DIC-HeLa datasetBaselines First, I wanted to set a baseline for each of the three datasets as close as possible to what the authors did. EM Dataset Baseline on the EM DatasetPhC-U373 Dataset Baseline on the PhC-U373 datasetDIC-HeLa Dataset Baseline on the DIC-HeLa DatasetQuestion #1: Larger tiles or larger batch size? Fixing pixels seen per update at 1M, let's compare batch size 4 with 512x512 tiles against batch size 16 with 256x256 tiles. EM Dataset Comparing larger tiles (orange) vs larger batch size (brown) on the EM datasetAs expected, training is noisier with smaller tiles, as are validation loss and IOU. PhC-U373 Dataset Comparing larger tiles (light green) vs larger batch size (dark green) on the PhC-U373 datasetInterestingly, smaller tiles seem a bit noisier and converge slower loss-wise, but the IOU seems higher. Could it be, though, that if masks are sparser in this dataset, more tiles are blank, causing the IOU to look artificially better earlier? DIC-HeLa Dataset Comparing larger tiles (salmon) vs larger batch size (brown) on the DIC-HeLa datasetThe same result occurs as with the EM dataset: everything is noisier. Conclusions and thoughts Why is everything noisier? We need to keep in mind that the input tiles are 256x256, but the output masks end up being only 68x68 pixels. The final loss is the average of each individual pixel’s loss, so you might think at first that fewer pixels result in a noisier loss. But we compensate with a larger batch size, so in the end each update averages 1M pixel losses, no matter the setting. Does this tell us there is more variation across samples in our dataset than across tiles? I conclude that larger tiles are better, just like the authors claim, but I’m still not sure why they lead to smoother training dynamics. Question #2: Do synthetic Weight Maps in the EM dataset really help? Comparing the weighted loss (orange) vs regular loss (brown) on the EM datasetTrain and validation loss look lower without weight maps, but the reason is that the loss function is different! The weight-map weighted loss is necessarily higher because we are scaling up border-adjacent pixel losses. However, the IOU metric tells a clearer story: there is no noticeable difference between having and not having this weighted loss. The weight maps turn out to be just a hacky inductive bias. My faith in the Holy Church of Gradient Descent remains intact, for now. Question #3: Would Adam converge faster than SGD? EM Dataset Comparing Adam (brown) vs SGD (orange) on the EM datasetAdam converges faster in training loss but seems to overfit faster, producing seemingly diverging validation loss. IOU seems unaffected. PhC-U373 Dataset Comparing Adam (dark green) vs SGD (light green) on the PhC-U373 datasetAdam really drops the ball here, with a massive loss spike and learning who knows what, by the looks of the IOU completely diverging. Let us reduce the learning rate from 1e-03 to 3e-04: Comparing Adam (dark green) vs SGD (light green) on the PhC-U373 datasetMuch better, though a loss spike remains in the same spot. It recovers quickly and achieves the best IOU from 2K steps onwards! DIC-HeLa Dataset Comparing Adam (brown) vs SGD (orange) on the DIC-HeLa datasetWe need to bring down the learning rate again from 1e-3 to 3e-4. Comparing Adam (brown) vs SGD (orange) on the DIC-HeLa datasetMuch nicer! Loss and IOU converge much faster too. Conclusions / thoughts Adam converges faster with a lower learning rate. Let us re-run the EM dataset with the lower learning rate, for good measure: Comparing Adam (brown) vs SGD (orange) on the EM datasetThe EM dataset is much smaller, so it seems to similarly overfit; that is perhaps not surprising. Conclusion I had fun doing this, and I experienced firsthand the reproducibility crisis in deep learning. If you are interested in getting better at this and exercising your critical thinking skills, I recommend you try this too. It is especially exciting when it comes to older papers because they can be more obscure, leaving more to figure out yourself, and at the same time they are easier to reproduce on today's consumer hardware. And if you are interested in reading about my next adventure reproducing older papers, watch this space!