How to add two vectors, fast

Dec 27, 2025

I’ve been building a Llama 3.2 inference engine aptly named forward (purely as an excuse to stop procrastinating and learn modern C++ and CUDA), from scratch.

Were I reasonable, I would not have decided to build a tensor library first, then a neural network library on top of it, and finally the Llama 3.2 architecture as the cherry on top. But here we are.

The first milestone was getting Llama to generate tokens correctly on the CPU first, with every activation of every layer matching the Huggingface Transformers inference output. Milestone achieved!

The next milestone, which I’m currently starting, is getting it to run as fast as I can on my NVIDIA GPU, an RTX 5090. The very first kernel I wrote is a timeless classic: adding two vectors element by element.

Walk with me. Wait, why are you running away.

Adding two vectors on the CPU

Let’s start with a baseline to convince ourselves whether using a GPU is worth it in the first place.

We want to add fairly large vectors, at least 134M elements each. This reflects the kinds of vector additions we will be doing during real-world Llama inference. Plus, each element will be a bfloat16 number, which for this article is just like a floating point number taking up 2 bytes of memory (16 bits).

On the CPU, that means creating a blank output vector of 134 million elements, iterating over the input vectors to add their elements, and write the result to the output vector.

(I’ve removed extraneous details like templating and broadcasting for legibility, but you can check the actual CPU implementation in the repo if you’d like your eyes to bleed.)

Vector<bfloat16, CPU> add(const Vector<bfloat16, CPU>& vector_a,

const Vector<bfloat16, CPU>& vector_b) {

assert(vector_a.length == vector_a.length && "the two vectors should be the same length");

Shape out_shape = vector_a.shape;

Vector<bfloat16, CPU> out{vector_a.shape}; // allocate the output vector

size_t total = out.size();

for (size_t idx = 0; idx < total; ++idx) {

// each element of the output vector is the sum of

// an element of a with an element of b

out[idx] = vector_a[idx] + vector_b[idx];

}

return out;

}Let's benchmark it. We will measure everything with a single throughput metric: FLOPs/s (floating point operations per second). Each addition is a floating point operation, so we will perform 134M of those and see how fast it is.

Benchmark Time FLOPs/s

BM_CPU_AddBf16/134M 135 ms 996.354 MFLOPs/sIt took 135 milliseconds to do all the additions, yielding just under 1 GigaFLOP per second of throughput. 1 GigaFLOP is 10^9 FLOPs (1 billion, in U.S. parlance). Not bad, right?

Actually pretty bad. We are using a single CPU thread to do all the additions sequentially, but the additions are independent of each other. Can we parallelize without breaking our brain too much? Let’s try using OpenMP, which only takes adding a line before our for loop. It will magically spawn a bunch of threads and split the work between them:

#pragma omp parallel for

for (size_t idx = 0; idx < total; ++idx) {

out[idx] = vector_a[idx] + vector_b[idx];

}Benchmark Time FLOPs/s

BM_CPU_AddBf16/134M 55 ms 2.44096 GFLOPs/sA 2.4x throughput increase with one line of code? Sign me up.

But surely we can do better using these expensive NVIDIA heating devices. Let’s dust off the CUDA books and make our GPU go brrr.

A simple CUDA kernel

__global__ void add_kernel(__nv_bfloat16* out, __nv_bfloat16* vector_a, __nv_bfloat16* vector_b, size_t n) {

auto idx = (blockIdx.x * blockDim.x) + threadIdx.x;

if (idx < n) {

out[idx] = vector_a[idx] + vector_b[idx];

}

}This looks pretty similar to our CPU version, but without the for loop. This function will run in a separate CUDA thread for each of the 134M elements—so all it needs to do is figure out which element idx it is responsible for, read one element from vector_a and one from vector_b, add them up, and store them in out.

CUDA lets us decide how to split the work, how many threads we need, etc. We need one thread per output element. Threads are organized in thread "blocks," which are laid out in a "grid"—don't worry about this, it's arbitrary, but we need to tell CUDA how big our thread blocks are and how many of them we need.

We can launch our kernel by converting from our bfloat16 type to CUDA’s equivalent __nv_bfloat16 and telling CUDA what launch grid configuration we want:

Vector<bfloat16, CUDA> add(const Vector<bfloat16, CUDA>& vector_a, const Vector<bfloat16, CUDA>& vector_b) {

assert(vector_a.length == vector_b.length && "the two vectors should be the same length");

size_t n_elements = vector_a.length;

Vector<bfloat16, CUDA> out{n_elements};

// each thread block will have 512 threads

size_t block_size = 512;

// we need enough thread blocks to process all the elements

size_t grid_size = (n_elements + block_size - 1) / block_size;

// Convert to device-native types for kernel call

auto* out_d = reinterpret_cast<__nv_bfloat16*>(out.data());

auto* a_d = reinterpret_cast<__nv_bfloat16*>(tensor_a.data);

auto* b_d = reinterpret_cast<__nv_bfloat16*>(tensor_b.data);

add_kernel<<<grid_size, block_size>>>(out_d, a_d, b_d, n_elements);

return out;

}Let us benchmark against the baseline:

Benchmark Time FLOPs/s

BM_CPU_AddBf16/134M 55 ms 2.44096 GFLOPs/s

BM_CUDA_AddBf16/134M 1.12 ms 119.307 GFLOPs/sJust over 1 millisecond! Our naive CUDA kernel is around 49x faster than the parallelized CPU version. But how good is that? How can we know whether our expensive heater is being utilized to its full potential?

Benchmarking against our potential

To answer that question, we have Nsight Compute, or its CLI version called ncu, which comes with the CUDA Toolkit. Let’s profile our kernel with it, and look at the first section, called GPU Speed Of Light Throughput:

Section: GPU Speed Of Light Throughput

----------------------- ----------- ------------

Metric Name Metric Unit Metric Value

----------------------- ----------- ------------

DRAM Frequency Ghz 13.79

SM Frequency Ghz 2.00

Elapsed Cycles cycle 1,045,192

Memory Throughput % 84.42

DRAM Throughput % 84.42

Duration us 521.02

L1/TEX Cache Throughput % 19.57

L2 Cache Throughput % 29.43

SM Active Cycles cycle 1,008,508.16

Compute (SM) Throughput % 19.20

----------------------- ----------- ------------SM stands for Streaming Multiprocessor, a collection of CUDA cores, a scheduler, and other details we do not care about right now. My GPU has 170 SMs, with 128 CUDA cores each.

Let's first focus on Memory Throughput and Compute (SM) Throughput. These percentages show how well our kernel utilizes available memory bandwidth and compute, respectively.

From the theoretical peak compute throughput, we are getting only 19.20%. That means, 80.80% of the time, our CUDA cores are sitting idle, waiting, not computing anything. Before we call NVIDIA and ask for an 80% refund, let’s ask ourselves. What are these precious CUDA cores waiting on?

Looking at the kernel again, we can focus on what it is actually doing:

__global__ void add_kernel(__nv_bfloat16* out, __nv_bfloat16* vector_a, __nv_bfloat16* vector_b, size_t n) {

auto idx = (blockIdx.x * blockDim.x) + threadIdx.x;

if (idx < n) {

out[idx] = vector_a[idx] + vector_b[idx];

}

}Each thread:

Loads one element from

vector_afrom global memory (commonly known as GPU VRAM) into a register.Loads 1 element from

vector_bfrom global memory into a register.Adds them up and stores the result in a register.

Stores the result from a register into

out, which is also global memory.

The CUDA cores only compute in step 3. Before that, it must wait for steps 1 and 2, and afterward, it must wait on step 4.

Adding two numbers takes 4–6 cycles, whereas memory operations to and from global memory (VRAM) take 200–400 cycles, orders of magnitude slower than the addition itself!

Fortunately, GPUs are excellent at hiding latency by running more threads while others wait on memory, but still.

There must be something more we can achieve with our fancy CUDA programming skills.

A fancy kernel

Let’s start with data movement. Each thread is currently loading a single bfloat16 value from each vector, but since we are making the trip to global memory anyway, why can’t we carry more stuff back? Like getting eight bfloat16 values at a time?

Loading 8 bfloat16 values in one go

The way we can do that is by pretending we want to load a 128-bit value, and then slicing it into our 8 bfloat16s. Memory is laid out linearly, so we can get away with that!

uint4 a_vec = reinterpret_cast<uint4*>(vector_a)[idx];We tell CUDA, “I want to read a pack of four 32-bit integers from global memory.” We then reinterpret this as a pointer to an array of bfloat16 values:

__nv_bfloat16* a = reinterpret_cast<__nv_bfloat16*>(&a_vec);

a[0] // get the first bfloat16 value

a[1] // the second one

// ... etc

a[7] // up until the last valueNow we can perform eight additions. Or can we get away with fewer instructions?

Doing two additions for the price of one

Turns out there is a packed bfloat16 type called __nv_bfloat162 (notice the 2 at the end, which means it contains two bfloat16s). We can add two __nv_bfloat162 values to do two additions in parallel with a single instruction this way. All we need is to change how we interpret the original uint4 packed value:

__nv_bfloat162* a2 = reinterpret_cast<__nv_bfloat162*>(&a_vec);Then, when adding __nv_bfloat162 values, we add two __nv_bfloat16s in parallel with a single instruction. Nice!

Our kernel now looks like this:

__global__ void xadd_bfloat16_kernel(__nv_bfloat16* out, __nv_bfloat16* vector_a, __nv_bfloat16* vector_b, size_t n) {

auto base = (blockIdx.x * blockDim.x) + threadIdx.x;

auto idx = base * 8; // each thread skips over 8 values

if (idx + 7 < n) {

// we load 8 bfloat16s disguised as 4 ints = 128 bits

uint4 a_vec = reinterpret_cast<uint4*>(vector_a)[base];

uint4 b_vec = reinterpret_cast<uint4*>(vector_b)[base];

// reinterpret as pairs of bf16s

__nv_bfloat162* a2 = reinterpret_cast<__nv_bfloat162*>(&a_vec);

__nv_bfloat162* b2 = reinterpret_cast<__nv_bfloat162*>(&b_vec);

uint4 out_vec;

__nv_bfloat162* out2 = reinterpret_cast<__nv_bfloat162*>(&out_vec);

out2[0] = a2[0] + b2[0]; // two additions in one

out2[1] = a2[1] + b2[1]; // another two

out2[2] = a2[2] + b2[2]; // yep

out2[3] = a2[3] + b2[3]; // we got our 8 additions!

reinterpret_cast<uint4*>(out)[base] = out_vec;

}

}Let’s benchmark and get ready to get paid the big bucks.

Benchmark Time FLOPs/s

BM_CPU_AddBf16/134M 55 ms 2.44096 GFLOPs/s

BM_CUDA_AddBf16/134M 1.12 ms 119.307 GFLOPs/s

BM_CUDA_AddBf16_Fancy/134M 1.11 ms 121.057 GFLOPs/sWhat? Only 10 microseconds faster after doing a PhD on the CUDA math API docs?

Compute-bound vs memory-bound kernels

How can we make sense of this? A useful concept captures the kind of kernel we are writing:

Arithmetic Intensity How much compute do we do for each byte we read or write?

In our case, it is one add instruction versus two 16-byte reads and one 16-byte write: 0.021 FLOPs/byte. We are basically just moving memory around the whole time, occasionally performing a tiny amount of compute.

It might seem wasteful, but there is little we can do about it—it is exactly what our kernel needs to do. Our kernel is memory-bound, meaning it is limited only by memory bandwidth (1.7 TB/s in my GPU), not compute.

Why isn’t the fancy kernel faster than the simple one?

Recall the GPU Speed of Light Throughput table?

Memory Throughput % 84.42We are utilizing the memory bandwidth close to optimally already, which is why loading more bytes at once makes little difference.

As per the additions with the __nv_bfloat162 packed type, we perform two additions with a single instruction, which bumps our Arithmetic Intensity to… 0.042 FLOPs/byte. Compute is such a tiny part of our kernel that it does not matter if we do it twice as fast. We are still memory bound.

Additionally, our more complex kernel uses more registers—a limited resource that, if abused, limits how many concurrent threads can run on an SM, so occupancy decreases. There is no free lunch.

Conclusion

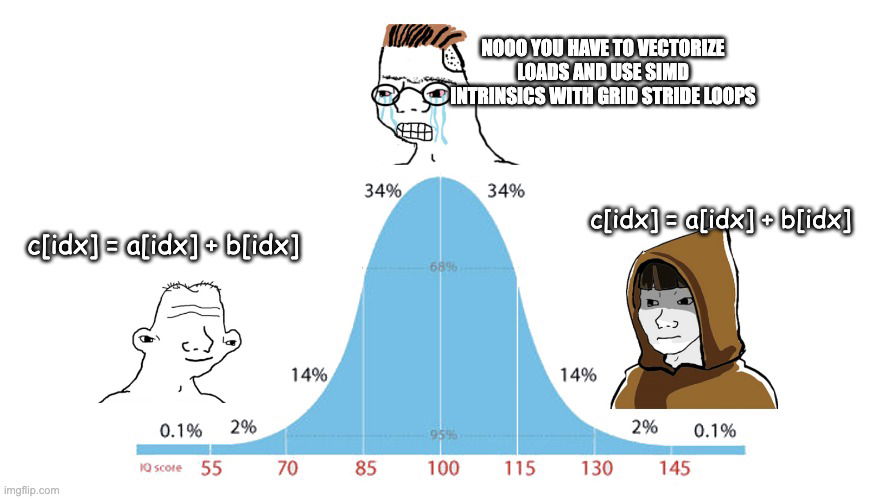

GPU optimization is both an art and a science, but it pays off to learn the specific hardware you are targeting, formulate and test hypotheses, and always measure everything.

Another win for the most widely applicable meme of all time, I guess.